Book Report: The Evolution of Beauty by Richard O. Prum

Current influences: Richard O. Prum, Patrik Schumacher, Recent visit to Mexico DF, All the newglassboxes ™

This review will focus on the thorough and important book by Richard Prum, The Evolution of Beauty. I will attempt to tie his ideas to recent trends in architecture and computation.

The recently released summary of Professor Prum’s research on beauty and nature was a challenging but rewarding read. Prum focuses on the second work of Darwin’s, “The Descent of Man”, and the role sexual selection and beauty play in evolution. Prum argues that we have ignored Darwin’s second book on sexual selection and beauty and focused on solely on his survival of the fittest portion in sciene and society. He persuasively argues that this has been an error in scientific thought. The reason I chose to read this book was after reading its review by the breakthrough institute, I was personally surprised to learn of an second theory of Darwin’s. Having taken a handful of biology, ecology, and environmental science courses at the university level I was intrigued I had never heard discussion of Darwin’s second book, since his first was extensively covered. The book is well written although at times it struggles to define its audience. Sometimes it feels like it is written for the broad public, others the educated public or his personal field. He also buries some of his more controversial application of the theory to human society toward the end of the book instead of working to blend it throughout. But all together it is an amazing summary of a career of working against prevailing survival of the fittest dogma.

Prum slowly builds a defense of the evolutionary impact of subjective desire through sexual selection in the first nine chapters of his book. He reviews decades of literature and crafts a narrative, primarily through birds, about mating rituals. He delves into the beauty and sexual agency of evolution through discussions of dance, morphological change in physical features and a surprising amount about duck dicks. The patterns and pageantry lead to the point that evolution does not just select through best function for survival. Evolution also is selected through subjective taste of mates by the animals themselves. He at one time calls the female Argus a “well-educated connoisseur evaluating one of the many extraordinary works available”. At another extraordinary part in the book he analyses the structures built for mating by bower birds that provide a safe place for the female gaze to linger on a mate. He explains how over time female mates may have selected this cultural practice into being by only considering males that create spaces for her to safely see their performance. His own research and papers by other professionals including Dr Donata, a professor of mine at Tulane, form a cohesive scientific argument for beauty and taste as a just as significant driver for evolutionary change.

As a student who was a few credits shy of an environmental science minor, all of this was fascinating, but as an architectural designer other things began to take over my interest. At a certain point in the book I realized I was no longer reading with my “science hat” on and was actively mining the text for points of friction between architecture and his revalations. In the twelfth and final chapter of the book Prum attempts to project what he has learned onto other fields, roughly 10 chapters after I had begun to do so. He is poetic and eloquent. Much of what I have written is an expansion and application specifically to architecture of what he writes. He calls for all of us to understand the ability of beauty to subvert honesty and provide its own value. He tells us to listen to all of Darwin and understand that “evolution is not merely about the survival of the fittest but also about charm and sensory delight in individual subjective experience.”

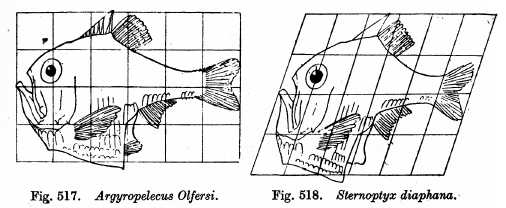

Architecture is no stranger to relying on biology to move forward. D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson’s studies on deformation are often shown in works on digital design and morphology. Projects by Calatrava and Studio Gang justify formal work through allusion to nature. Design iteration, optimization and evolutionary fitness solving have become interchangeable terms in discussions at computational design conferences. David Benjamin has called for the century of biology and his work and that by Achim Menges’ frequently hold biology as a paradigm of fitness optimization. Patrik Schumacher has decided that the whole world can and should be solved through the survival of the fittest notion of a completely free market. I adore much of the built work that has come from these practitioners, particularly Achim and The Living. I have openly gushed about each of their work at different times but the survival of the fittest based thinking that has come with it leaves little room for the surplus that makes architecture a culture shifting force. This rise in architecture of the goal of the singular desired output of fitness/efficiency without room for the shifting individual subjective experience is why Prum’s work is perfectly timed for today’s discourse.

Prum’s book gives architecture another way to look at evolution and nature as more than a means to cut cost but as a place to see value in beauty and excess. A striking study of the power of ornament was comparison x-rays of a similar birds wing bones with the unique bone shape of the male Club-winged manakin’s wings that hinder its ability to fly for a more beautiful mating performance. The bones have deformed over time adding notches and bumps making flight more difficult but creating reverberation when rubbed together like a cricket adding additional sound to the the mating dance. Prum’s study of bower birds also presents a Bernard Tschumi like study of bower birds and how bowers are created by males to provide females an escape from the male’s own sexual aggression. His studies of the formal structure and the behavior created by it show the ability for ornamental spaces to create cultural changes. Prum writes the “bower has no function beyond its use as a seduction theater – an ornamental stage for male sexual display.” The bower, like a theater, defines audience (female) and performer (male) and creates a structure to allow the female to easily fly away. This keeps the female from being unwillingly mated with until they have judged the entire performance, something exceptional in the animal kingdom. The Great Bowerbird is particularly interesting as it lines the entry to its bower with shells increasing in size as they get further away from the bower creating a forced perspective. This trick actually makes the male bird look smaller to the approaching the female. Better creators of the false perspective have better mating success suggesting that desire for beauty (perspective) may be more important than mating fitness (size). The most beneficial choice for efficiency of daily life is balanced with the value of beauty, agency, and seduction in evolution. This balance should not be lost in the current optimization and computational push.

Prum’s book is a step towards opening architecture back up to discussions of beauty, emotion, and ornament as apart of the whole experience of architecture. Optimization for efficiency of daily living will not create the architectural equivalency of the vibrancy of the peacocks tail, the excitement of the mating dance of the bird of paradise, or the sweet melody of a mating call. Aesthetic subjective choice for both beauty and function through curation by empowered humans will.